Are Law Firms Repeating the Mistakes of the 1990s?

One topic we discussed at Ari Kaplan's breakfast this morning was how should firms decide where to deploy AI.

The question itself seems to be based on a flawed premise and reveals several problems.

For the last few years, most firms have been making these decisions based on political power rather than long-term strategy. Partners who are rainmakers drive what AI gets procured and where it's used. This is entirely contrary to what firms should be doing — either (a) strategically examining their goals for the future and deploying AI to support those goals, or (b) opportunistically seeking out where AI generates a return on investment and scaling where deployment yields results.

As the topic was discussed, a thought occurred to me — generative AI adoption mirrors how law firms adopted PCs in the 1990s.

The Era of the "Dusty Monitor"

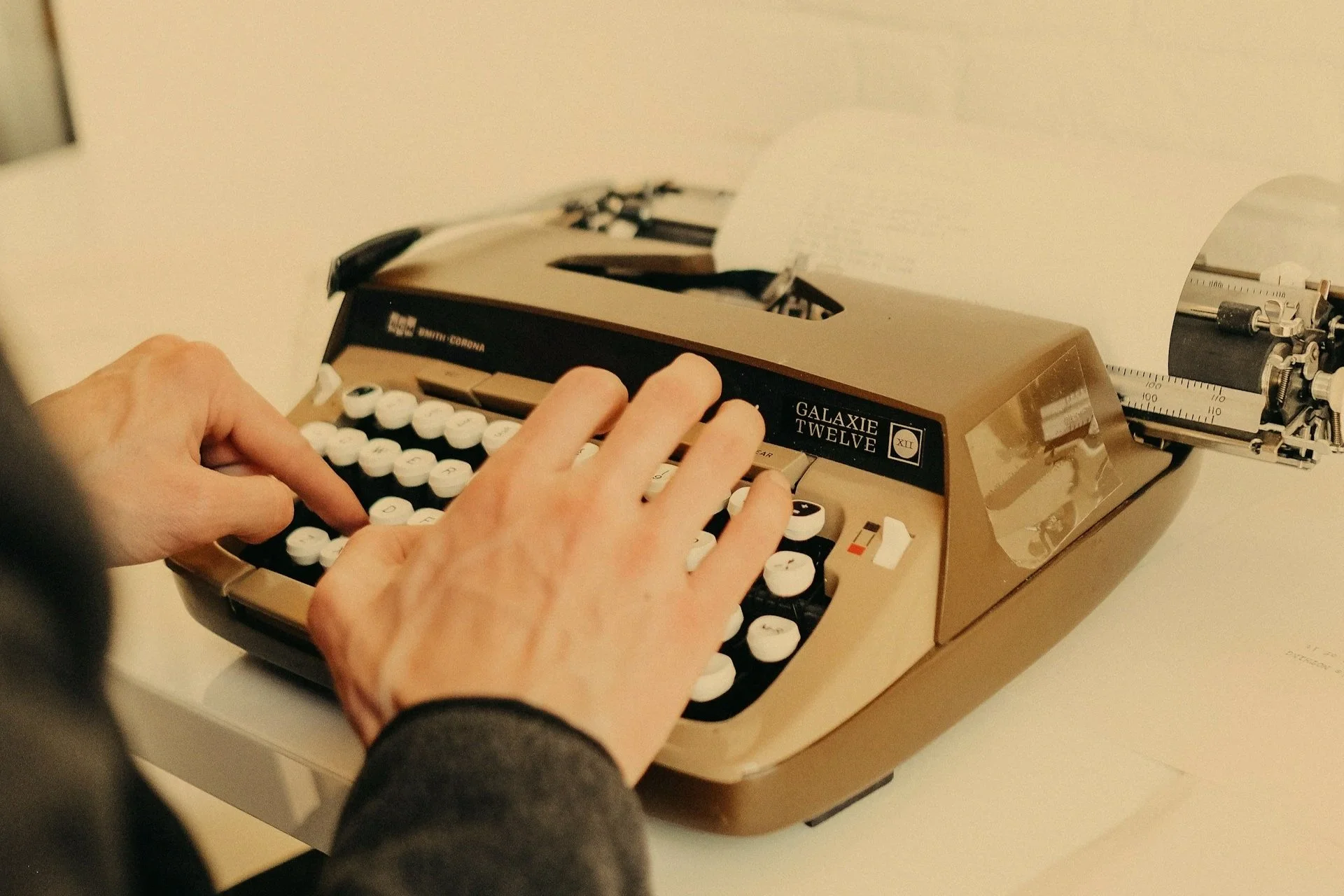

In the early to mid-1990s, PCs weren't particularly useful for most lawyers. Firms bought them for prestige, FOMO, or because clients expected it. Historical accounts describe computers being unloaded "fire-brigade style" and left in piles, or remaining in original boxes for months. Even where they were used, they often functioned as glorified typewriters.

Some firms made lawyers "explain how they would use a PC" before granting them one — a kind of rationing system since PCs cost thousands of dollars back then. Meanwhile, wealthier firms saw partners demand PCs as status symbols even when they had no intention of using them. The monitor sat collecting dust while the partner continued using a dictaphone and secretaries.

The "dusty monitor" became the symbol of that era: capital expenditure without operational return.

Gen AI’s "Idle Licenses"

In 2024 and 2025, the equivalent of the “dusty monitor” was the digital “idle license”.

Many firms sign contracts for enterprise tools, creating theoretical capacity for AI-driven work, but usage and adoption were low. One international firm told us their adoption was “in the single digits [of percentages]”. The licenses were active, the bills were paid, but lawyers weren't logging in.

Just as the 90s partner stared at a C:> prompt wondering what to type, we saw lawyers stare at a blinking cursor in a chatbot, unsure how to get legal work done.

Why the low adoption? Some lawyers are waiting for tools to mature. Others don't trust outputs that might hallucinate. The deeper issue is that firms bought the technology before understanding what problems it would solve.

Waiting for the "Killer App"

In the early 90s, before emails and the internet, most PCs were just glorified typewriters. The PC didn't become essential for lawyers until it was connected. Emails and online research provided the killer use cases.

It was connectivity that justified the PC hardware.

What will make Gen AI indispensible? What is the “killer app” for LLMs?

Adoption of PCs in the 90s happened on two tracks. Back-office infrastructure — servers, networks, document management — scaled quietly without much lawyer involvement. But front-office adoption — the PC on every lawyer's desk — only took off when it solved direct productivity problems that lawyers themselves experienced.

Gen AI may be seeing the same pattern today:

Gen AI that is being deployed behind the scenes for document processing, data extraction, and research preparation is scaling with usage.

Front-office adoption — e.g. chatbots, collaboration platforms, tools that lawyers interact with directly — often stalls.

Increasing Client Pressure

Just as it were in the 1990s when corporate counsels began demanding that firms adopt technology to improve communication and transparency — emails, faxes, and digital billing — according to Thomson Reuters, today, 59% of corporate legal clients want their outside firms to use Gen AI.

Since there is not yet a killer app for Gen AI and since Gen AI tend to reduce the number of billable hours, it would appear that most firms are buying licenses to Gen AI tools in order to look efficient, rather than be efficent.

These top-down procurement decisions — buying enterprise licenses and rolling them out to every lawyer as innovation theatre — seem to lead to patchy adoption across many firms. There is almost an unspoken, collective hope that "we'll figure out what to do with it later".

The Right Question to Ask

The transition from "having a PC" to "using PCs" took 5 years and required a generational shift. The transition from "having AI" to "using AI" is moving faster, but feels equally painful.

Just as a PC in 1992 was raw computing power waiting for the right applications to make it useful, LLMs in 2026 are raw capability waiting for the right systems and workflows to unlock their value. A PC became indispensable not because of the processor itself, but because of email clients, word processors, and research databases built on top of it. Similarly, LLMs will become indispensable not because of their text generation abilities and ostensible analytical prowess, but because of what gets built on top of them.

So, how do we solve the “idle licenses” problem? Is it finding the killer app, or:

Maybe there is not a single killer app. Maybe it’s the combination of many smaller use cases that together justify the investment. The 90s taught us that email was transformative, but so was the combination of word processing, research databases, document management, and billing systems.

Maybe we're still waiting for the breakthrough. Something that fundamentally changes how legal work gets done, the way connectivity transformed the isolated PC into an essential tool.

Maybe we are measuring the wrong things. If AI can do work that neither saves costs nor increases revenue — if it just makes people "feel productive" without business impact — perhaps that reveals which work was never valuable in the first place.

In the 90s, the killer apps emerged when people identified what was preventing lawyers from doing their best work for clients, then built solutions on top of the PC hardware.

Perhaps we should stop asking where should we deploy AI? Because the answer should be obvious once you have answered the question “what prevents our lawyers from doing their best work for clients?”